- Home

- Friedrich Holderlin

Hyperion Page 3

Hyperion Read online

Page 3

I gave mine to his servant and we walked onward by foot.

It served us right, I began, as we walked together arm in arm out of the woods; why did we hesitate so long and pass each other by until misfortune brought us together?

Then I must tell you, replied Alabanda, that you are the guiltier one, the colder one. I rode after you today.

Glorious man! I cried, you shall see! You shall never surpass me in love.

We became ever more intimate and joyful together.

Nearby the city we passed a well-built caravansary that reposed among burbling fountains and fruit trees and fragrant meadows.

We decided to stay the night there. We sat together for a long time by the open windows. High, spiritual silence embraced us. Earth and sea were blissfully mute, like the stars that hung above us. Barely did a breeze from the sea drift into the room and play tenderly with our light, or the mightier tones of distant music penetrate to us while the thundercloud lulled itself to sleep in the bed of the ether and now and again sounded distantly through the silence, like a sleeping giant when he breathes more heavily in his terrible dreams.

Our souls were drawn near to each other all the more strongly because they had been closed off against our will. We encountered each other like two brooks that roll from the mountain and hurl from themselves the load of earth and stone and rotten wood and the whole inert chaos that holds them back so as to clear the way to each other and to break through to the point where, seizing and seized with equal force, united in one majestic river, they now begin their journey into the wide sea.

He, driven by destiny and the barbarity of men from his own house and cast to and fro among strangers, embittered and untamed from his early youth, and yet with his inner heart full of love, full of longing to break through the coarse husk into a congenial element; I, already so deeply cut off from everything, so utterly and resolutely foreign and alone among men, so laughably accompanied in my heart’s dearest melodies by the clang of the world’s bells; I, the antipathy of all the blind and the lame, and yet too blind and lame for myself, so profoundly burdensome to myself in all that was distantly akin to the shrewd and the sophists, the barbarians and the would-be wits – and so full of hope, so full of the unique expectation of a more beautiful life.

Was it not necessary that the two youths embrace each other in such joyful, impetuous haste?

O you, my friend and comrade-in-arms, my Alabanda, where are you? I almost believe that you have crossed to the unknown land, to repose, have become again as you once were, when we were still children.

At times when a storm approaches over me and dispenses its divine powers among the woods and the crops, or when the waves of the tide play with one another, or a chorus of eagles soars about the mountain summits where I wander, my heart can stir as if my Alabanda were not far; but more visibly, more presently, more unmistakably he lives in me wholly as he once stood, a fiery, severe, terrible prosecutor, when he enumerated the sins of the century. How my spirit awakened in its depths, how the thundering words of inexorable justice rolled over my tongue! Like messengers of Nemesis, our thoughts traversed the whole earth and purified it until not a trace of a curse remained.

We called the past, too, before our judge’s bench; proud Rome did not frighten us with its glory, and Athens did not win us over with its youthful bloom.

As storms blow exultantly, unceasingly onward through forests, over mountains, so our souls pressed forward in colossal projects; not that we had created our world in an unmanly fashion, as with a magic word, and, childishly inexperienced, reckoned with no resistance; Alabanda was too wise and too brave for that. But even effortless enthusiasm is often warlike and shrewd.

One day is especially present to me.

We had gone to the countryside together, sat intimately embracing in the dark shade of the evergreen laurel, and looked together in our Plato, where he speaks with such wondrous sublimity of growing old and rejuvenation, and our eyes rested now and again on the mute, leafless landscape, where the sky played more beautifully than ever with its clouds and sunshine around the autumnal, sleeping trees.

We then spoke much of Greece today, both with bleeding hearts, for the degraded soil was Alabanda’s fatherland too.

Alabanda was unusually moved.

When I look at a child, he cried, and think how shameful and corrupting is the yoke that it will bear, and that it will starve as we do, that it will seek men as we do, search as we do for the beautiful and the true, that it will pine away fruitlessly, because it will be alone as we are, that it – O take your sons from the cradle, compatriots, and cast them into the river, so as to rescue them at least from your disgrace!

Surely, Alabanda! I said, surely things will change.

How? he replied; the heroes have lost their glory, the wise men their apprentices. Great deeds, when a noble people does not pay heed to them, are no more than a powerful blow to a numb brow, and high words, when they do not resound in high hearts, are like a dying leaf that rustles down into the muck. What will you do?

I will take a shovel and fling the muck into a pit, I said. A people in which spirit and greatness engender no more spirit and no more greatness has nothing more in common with others who are still men, has no more rights; and it is an empty farce, a superstition, to continue honoring such will-less corpses as if a Roman heart were in them. Away with them! The withered, rotten tree may not stand where it stands; it steals light and air from the young life that ripens for a new world.

Alabanda flew to me, embraced me, and his kisses entered my soul. Brother in arms! he cried, dear brother in arms! O now I have a hundred limbs!

I have finally found my melody, he went on, with a voice that moved my heart like a battle cry – nothing more is needed! You have spoken a glorious word, Hyperion! What? Shall the god be dependent upon the worm? The god in us, for whose course infinity opens, shall stand and wait until the worm moves out of his way? No! no! We do not ask if you will it! You never will anything, you slaves and barbarians! We do not even seek to improve you, for it is in vain! we seek only to ensure that you move out of the way of the triumphant course of mankind. O! Someone ignite a torch for me, so that I may burn the weeds from the heath! Someone prepare the mine for me, so that I may blast the inert clods from the earth!

When possible, one pushes them gently aside, I broke in.

Alabanda fell silent for a while.

I find my pleasure in the future, he finally resumed, and fervently grasped both my hands. Thank god! I will come to no common end. To be happy means to be sleepy in the mouth of slaves. To be happy! I feel as if I had pap and tepid water on my tongue when you slaves talk to me of being happy. So inane and so hopeless is everything for which you give up your laurel crowns, your immortality.

O holy light that moves restlessly above us, powerful in its immense kingdom, and imparts its soul to me, too, in the rays that I drink – may your happiness be mine!

The sons of the sun are nourished by their deeds; they live by triumph; their own spirit emboldens them, and their strength is their joy. –

The spirit of this man often took hold of me so forcefully that I might have felt ashamed of being carried away as though light as a feather.

O heaven and earth! I cried, this is joy! – These are different times, this is no tone from my childish century, this is not the soil upon which the heart of man gasps under the slave-driver’s whip – Yes! yes! with your glorious soul, O man! you will save my fatherland!

This I will, he cried, or perish.

From that day on we became ever holier and dearer to each other. Profound, indescribable seriousness had arisen between us. But we were only all the more blissful together. Each of us lived only in the eternal fundamental tones of his being, and we strode austerely from one great harmony to another. Our common life was full of glorious severity and boldness.

Why have you become so poor in words? Alabanda asked me once with a smile. In the hot regions, said I,

nearer to the sun, even the birds do not sing.

But all moves up and down in the world, and man, with all his gigantic strength, holds fast to nothing. I once saw a child stretch out its hand so as to grasp the moonlight; but the light continued calmly on its path. So we stand and struggle to halt ever-changing destiny.

O if only we could watch it as serenely and meditatively as we watch the course of the stars!

The happier you are, the less it costs to destroy yourself, and blessed days such as Alabanda and I lived are like a precipitous cliff where your travel companion need only touch you to hurl you inadvertently down over the sharp jags into the shadowy depths.

We had made a glorious journey to Chios, had found a thousand pleasures in each other. Like breezes over the sea’s surface, the friendly enchantments of nature ruled over us. With joyful astonishment we gazed at each other without speaking a word, but our eyes said, I have never seen you thus! So exalted were we by the powers of earth and heaven.

During the journey, we had also argued with cheerful fervor over many things; I had, as usual, taken heartfelt pleasure in watching this spirit on its bold, wayward course, as it followed its path so erratically, with such unbounded joy, and yet for the most part so surely.

When we disembarked, we hastened to be alone.

You can convince no one, I said now with profound love, you persuade men, you win them over before you begin; one cannot doubt when you speak, and he who does not doubt is not convinced.

Proud flatterer! he cried in reply – you lie! but it is right that you remind me! only too often have you made me irrational! Not for all crowns would I free myself from you, but it often worries me that you should be so indispensable to me, that I am so fettered to you; and see, he went on, since you have me entirely, you shall also know everything about me! until now, amidst all the glory and joy, we have not thought to look back at the past.

He told me now his destiny, and I felt as if I saw a young Hercules in battle with Megaera.

Will you now forgive me, he concluded the tale of his adversity, will you now be calmer if I am often harsh and offensive and insufferable?

O be silent, be silent! I cried, profoundly moved; the essential is that you are still here, that you preserved yourself for me!

Yes indeed! For you! he cried, and it delights my heart that I am still palatable fare for you. And should I taste at times like a crab apple to you, press me for as long as it takes until I am drinkable.

Let me be! Let me be! I cried; I resisted in vain; the man turned me into a child; and I did not conceal it from him; he saw my tears, and woe to him if he were not permitted to see them!

We revel, Alabanda now resumed, we slay time in intoxication.

We spend our bridegroom days together, I cried, exhilarated. Thus it may well sound as if we were in Arcadia. – But to return to our earlier conversation.

You concede too much power to the state. It may not demand what it cannot coerce. But what love gives, and spirit, cannot be coerced. Either the state leaves that untouched, or we take its law and nail it to the pillory! By heaven! he who would make the state into a school of mores does not know his sin. The state has always been made into hell because man wanted to make it into his heaven.

The coarse husk around the kernel of life and nothing more – that is the state. It is the wall around the garden of human fruits and flowers.

But what help is the wall around the garden when the soil lies barren? Only the rain from the heavens helps then.

O rain from the heavens! O enthusiasm! You will bring us again the springtime of peoples. The state cannot command you to come. But may it not disturb you, and then you will come with your all-powerful ecstasies, you will envelop us in golden clouds and bear us upward above mortality, and we will marvel and ask if it is still we, we destitute creatures who asked the stars if a spring bloomed for us up there – do you ask me when this will be? It will be when the darling of time, the youngest, most beautiful daughter of time, the new church, will emerge out of these besmirched, antiquated forms, when the awakened feeling of the divine will bring man his divinity again, and restore beautiful youth to his breast, when – I cannot herald it, for I have only a vague presentiment of it, but it will come, surely, surely. Death is a messenger of life, and that we now sleep in our hospitals testifies to imminent healthy awakening. Then, only then shall we, shall the element of our spirits, be found.

Alabanda fell silent and gazed at me for a while in astonishment. I was carried away by infinite hopes; divine powers bore me forth like a cloudlet. –

Come! I cried, and grasped Alabanda by his garment – come, who can endure any longer in this prison that benights us?

Come where, my enthusiast, replied Alabanda dryly, and a shadow of mockery seemed to glide over his face.

I felt as if I had fallen from the clouds. Go! I said – you are a small man!

In the same instant several strangers entered the room. They were striking figures, mostly gaunt and pale as far as I could see in the moonlight, and calm, but in their countenances was something that pierced the soul like a sword, and it was as if one stood before omniscience; one would have doubted that this was the exterior of natures in need, if here and there the killed emotion had not left its traces.

One of them in particular struck me. The stillness of his features was the stillness of a battlefield. Fury and love had raged in this man, and the understanding shone over the ruins of his heart like the eye of a hawk that sits upon destroyed palaces. Profound contempt was on his lips. One suspected that this man harbored no insignificant intention.

Another may have owed his calm more to a natural hardness of heart. One found in him almost no trace of violence perpetrated by his will or by destiny.

A third may have wrung his coldness from life more by strength of conviction, and perhaps still often stood in battle with himself, for there was a secret contradiction in his being, and it seemed to me as if he needed to keep watch over himself. He spoke the least.

Alabanda sprang up like bent steel upon their entrance.

We sought you, one of them cried.

You would find me, he said, laughing, even if I were hiding in the center of the earth. They are my friends, he added, turning to me.

They seemed to eye me rather sharply.

This is also one of those who would like to have a better world, Alabanda cried after a while, pointing to me.

This is in earnest? one of the three asked me.

It is no joke, to better the world, said I.

You have said much with one utterance! one of them cried. You are our man! added another.

You, too, think as I do? I asked.

Ask what we do! was the answer.

And if I asked?

Then we would say to you that we are here to clear the earth, that we gather the stones from the field and smash the hard clods of earth with the hoe and dig furrows with the plow, and grasp the weed by the root and cut it through at the root and tear it out together with the root, so that it may wither in the sun’s blaze.

Not that we might reap, another broke in; for us the reward comes too late; for us the harvest ripens no more.

We are at the evening of our days. We often went astray, we hoped much and did little. We risked rather than reflected. We were eager to reach the end and trusted in luck. We spoke much of joy and pain, and loved and hated both. We played with destiny and it did likewise with us. From the beggar’s staff to the crown, it hurled us up and down. It swung us as one swings a glowing censer, and we glowed until the coal turned to ash. We have ceased to speak of luck and misfortune. We have grown beyond the middle of life where it is green and warm. But it is not the worst that outlives youth. From hot metal, the cold sword is forged. They say, too, that the grapes that thrive on extinguished, dead volcanoes make no bad wine.

We say this not for our sake, another cried, now somewhat more hastily – we say it for your sakes! We beg for no man’s heart. For we ne

ed not his heart, his will. For he is in no case against us, for all is for us, and the fools and the shrewd and the simple and the wise and all vices and all virtues of coarseness and cultivation stand, without having been hired, in our service, and help us blindly toward our goal – we only wish that someone would partake in the pleasure of it, and therefore we choose the best among our thousand blind helpers so as to make them into seeing helpers – but if no one wants to dwell where we built, it is not our fault or our loss. We did our part. If no one gathers where we plowed, who blames us for it? Who curses the tree when its apple falls into the mire? I have often told myself, you sacrifice to rottenness, and yet I finished my day’s work.

These are impostors! all the walls cried to my sensitive awareness. I felt like someone suffocating in smoke, who breaks down doors and smashes in windows to escape – so fiercely did I thirst for air and freedom.

They soon saw what an uncanny feeling had come over me, and broke off. The day was already dawning as I stepped out of the caravansary where we had been together. I felt the morning breeze like balsam on a burning wound.

I was already too irritated by Alabanda’s mockery not to be utterly disconcerted by his enigmatic acquaintances.

He is wicked, I cried, yes, he is wicked. He feigns boundless trust and lives with such men – and conceals it from you.

I felt like a bride when she learns that her beloved lives in secret with a whore.

O it was not the pain that one may nurse, that one bears in the heart like a child and sings into slumber with the tones of the nightingale!

Like a furious snake when it moves implacably up the knees and the loins and coils around all the limbs, and sinks its venomous fangs now into the breast and now into the nape of the neck – thus was my pain, thus did it clasp me in its terrible embrace. I summoned my utmost heart and struggled for great thoughts to keep calm; for a few moments I succeeded, but now I was also strengthened for rage, now, as if it were arson fire, I killed every spark of love in me.

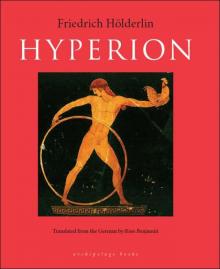

Hyperion

Hyperion