- Home

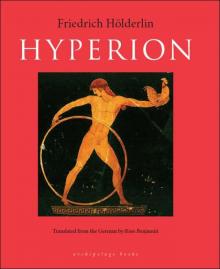

- Friedrich Holderlin

Hyperion

Hyperion Read online

Friedrich Hölderlin

HYPERION

or

THE HERMIT IN GREECE

. . .

Translated from the German by Ross Benjamin

archipelago books

English Translation copyright © 2008 Ross Benjamin

First Archipelago Edition 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hölderlin, Friedrich, 1770-1843.

[Hyperion. English]

Hyperion, or, The hermit in Greece / by Friedrich Holderlin ;

translated by Ross Benjamin.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-9793330-2-6 (alk. paper)

I. Benjamin, Ross. II. Title.

PT2359.H2A713 2008

833'.6 – dc22 2008000964

Archipelago Books

232 Third Street, #A111

Brooklyn, NY 11215

www.archipelagobooks.org

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales and Distribution

www.cbsd.com

This publication was made possible by the generous support of Lannan Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York State Council for the Arts, a state agency. The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut, funded by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

HYPERION

. . .

CONTENTS

FIRST VOLUME

PREFACE

FIRST BOOK

SECOND BOOK

SECOND VOLUME

FIRST BOOK

SECOND BOOK

FIRST VOLUME

Non coerceri maximo, contineri minimo, divinum est.

. . .

Not to be confined by the greatest,

yet to be contained by the smallest, is divine.

PREFACE

I would gladly promise this book the love of the Germans. But I fear that some of them will read it as a compendium and concern themselves too much with the fabula docet,* whereas others will take it too lightly, and both sides will not understand it.

He who merely sniffs my flower does not know it, and he who plucks it merely so as to learn from it also does not know it.

The resolution of dissonances in a certain character is neither for mere thought nor for empty pleasure.

The setting where what follows occurred is not new, and I confess that I was once childish enough to attempt to alter the book in this regard, but I convinced myself that it was the only setting appropriate to Hyperion’s elegiac character and felt ashamed that the likely judgment of the public had made me so excessively pliant.

I regret that for now the evaluation of the book’s plan is not yet possible for everyone. But the second volume shall follow as quickly as possible.

*“[That which] the fable teaches.” [Translator]

FIRST BOOK

HYPERION TO BELLARMIN

The dear soil of my fatherland again brings me joy and sorrow.

Every morning I am now on the heights of the Corinthian Isthmus and, like a bee among flowers, my soul often flies back and forth between the seas that, to the right and left, cool the feet of my glowing mountains.

One of the two gulfs especially should have delighted me, had I stood here a millennium ago.

Between the glorious wilderness of Helicon and Parnassus where daybreak plays among a hundred snow-covered peaks and the paradisiacal plain of Sicyon, the shining gulf surged like a triumphant demigod toward the city of joy, youthful Corinth, and poured out the captured riches of all regions before its darling.

But what is that to me? The cry of the jackal that sings its wild dirge among the stone heaps of antiquity startles me out of my dreams.

Joy to the man whose heart is delighted and strengthened by a flourishing fatherland. I feel as if I were cast into the mire, as if the coffin lid were slammed shut over me, whenever someone reminds me of my own; and whenever someone calls me a Greek, I feel as if he throttled me with a dog collar.

And see, my Bellarmin! when at times such an utterance escaped me, and perhaps in my rage a tear also came to my eye, along came the wise men who so enjoy lurking among you Germans, the wretches for whom a suffering soul is the perfect occasion to impart their sayings, and they indulged themselves and presumed to say to me: Do not lament, act!

O, had I only never acted! By how much hope would I be richer! –

Yes, only forget that there are men, my starving, troubled, ceaselessly agitated heart! and return whence you came, into the arms of nature, the changeless, the silent and the beautiful.

HYPERION TO BELLARMIN

I have nothing that I may call my own.

Distant and dead are my loved ones, and I hear nothing more of them from any voice.

My business on earth is over. I set to work full of will; I bled over my labor, and made the world not a penny richer.

Ingloriously and alone I return, and wander through my fatherland that lies all around me like a garden of the dead, and perhaps awaiting me is the knife of the hunter, who holds us Greeks for his pleasure just as he does the game of the forest.

But you still shine, sun of the heavens! You still grow green, holy earth! Still the rivers rush into the sea, and shady trees rustle at midday. Spring’s song of bliss sings my mortal thoughts to sleep. The fullness of the all-living world nourishes and satiates my starving being with intoxication.

O blessed nature! I do not know what befalls me when I raise my eyes before your beauty, but all the pleasure of heaven is in the tears that I weep before you, the beloved before his beloved.

My whole being falls silent and hearkens when the tender surge of the air plays about my breast. Often, lost in the wide blue, I look up at the ether and into the holy sea, and I feel as if a kindred spirit opened its arms to me, as if the pain of solitude dissolved into the life of the divinity.

To be one with all – that is the life of the divinity, that is the heaven of man.

To be one with all that lives, to return in blessed self-oblivion into the All of nature, that is the summit of thoughts and joys, that is the holy mountain height, the place of eternal repose, where the midday loses its swelter and the thunder its voice and the boiling sea resembles the billowing field of grain.

To be one with all that lives! With these words virtue removes its wrathful armor, the spirit of man lays its scepter aside and all thoughts vanish before the image of the world’s eternal unity, just as the rules of the struggling artist vanish before his Urania; and iron fate abdicates its power, and death vanishes from the union of beings, and indivisibility and eternal youth bless and beautify the world.

I often stand at this height, my Bellarmin! but a moment of reflection hurls me down. I reflect and find myself as I was before, alone, with all the pains of mortality; and the asylum of my heart, the world’s eternal unity, is gone; nature closes her arms and I stand like a stranger before her and do not comprehend her.

O! had I never gone to your schools. Knowledge, which I pursued down into the shaft, and from which in my youthful folly I expected confirmation of my pure joy, has corrupted everything for me.

Among you I became so perfectly rational, learned so thoroughly to distinguish myself from what surrounds me that I am now isolated in the beautiful world, cast out of the garden of nature, where I grew and bloomed, and am drying up under the midday sun.

O man is a god when he dreams, a beggar when he thinks, and when enthusiasm is gone, he stands there like a wayward son whom the father has driven out of the house and regards the meager pennies that pity gave him for t

he journey.

HYPERION TO BELLARMIN

I thank you for asking me to tell you of myself, for recalling times past to my memory.

My desire to live nearer to where I played as a youth also drove me back to Greece.

As the worker falls into refreshing sleep, so my troubled being sinks often into the arms of the innocent past.

Peace of childhood! heavenly peace! how often I stand still before you in loving contemplation and attempt to fathom you! But we have concepts only of what was once bad but has been made good; of childhood, of innocence we have no concepts.

When I was still a serene child, and knew nothing of all that surrounds us, was I not then more than I am now, after all the troubles of my heart and all the reflection and struggle?

Yes! the child is a divine being so long as it has not been dipped into the chameleon colors of men.

The child is wholly what it is, and that is why it is so beautiful. The compulsion of the law and fate does not touch it; in the child is only freedom.

In the child is peace; it is not yet at odds with itself. Wealth is in the child; it knows not its heart, nor the destitution of life. It is immortal, for it knows nothing of death.

But this men cannot bear. The divine must become like one of them, must learn that they, too, are there; and before nature drives it out of its paradise, men coax and drag it out into the field of the curse, so that it, like them, shall slave away in the sweat of its brow.

But beautiful, too, is the time of awakening, so long as we are not awakened at an untimely moment.

O, they are holy days when our heart first tests its wings, when we, full of swift, fiery growth, stand in the glorious world like the young plant that opens itself up to the morning sun and stretches its little arms toward the infinite heavens.

How I was driven to the mountains and to the seashore! O, how I often sat with pounding heart on the heights of Tina and watched the falcons and cranes and the bold, joyous ships as they vanished below the horizon! There, below the horizon! I thought. There you, too, will one day wander; and I felt like a man who has been languishing in the heat when he plunges into the cooling bath and splashes the foaming water over his brow.

Sighing, I turned back then toward my home. If only my school years were over, I often thought.

Dear boy! They are still far from over.

That man in his youth believes the goal lies so near! It is the most beautiful of all deceptions with which nature props up the weakness of our being.

And often when I lay among the flowers and basked in the tender spring light and looked up into the clear blue that embraced the warm earth, when I sat in the bosom of the mountain under the elms and willows after a refreshing rain, when the branches still trembled from the touches of the heavens, and golden clouds moved over the dripping woods; or when the evening star, full of peaceful spirit, rose with the ancient youths and the other heroes of the heavens, and I saw how the life in them moved forth through the ether in eternal, effortless order, and the peace of the world surrounded and delighted me, so that I paid heed and hearkened, without knowing what befell me – Do you love me, dear father in heaven? I asked then softly, and felt his answer so certainly and blissfully in my heart.

O you to whom I called, as if you were above the stars, whom I named creator of heaven and earth, friendly idol of my childhood, you shall not be angry that I forgot you! – Why is the world not destitute enough to make us seek Another outside of it?*

O if glorious nature is the daughter of a father, is not the daughter’s heart then his heart? Her innermost being, is it not He? But then, do I have it? do I know it?

It is as if I saw, but then I am seized with fright again, as if it were my own form that I saw; it is as if I felt it, the spirit of the world, like a friend’s warm hand, but I awaken and realize that I was holding my own finger.

HYPERION TO BELLARMIN

Do you know how Plato and his Stella loved each other?

Thus I loved, thus was I loved. O I was a fortunate boy!

It is pleasant when like joins like, but it is divine when a great man brings lesser men up to him.

A friendly word from the heart of a valiant man, a smile in which the consuming glory of the spirit hides itself, is little and much, like a magical password that conceals death and life in its simple syllable; it is like spiritual water that wells from the depths of the mountains and imparts to us the secret strength of the earth in its crystalline drops.

How I hate, on the other hand, all the barbarians who imagine that they are wise because they no longer have a heart, all the coarse monsters who kill and destroy youthful beauty a thousand times over with their narrow, irrational discipline.

Dear God! This is the owl seeking to drive the young eagles out of the nest and show them the way to the sun.

Forgive me, spirit of my Adamas! for thinking of these men before thinking of you. That is the profit we gain from experience, that we think of nothing excellent without its deformed opposite.

O if only you were eternally present to me, with all that is akin to you, mourning demigod whom I recall! Whomever you embrace with your calm and strength, my vanquisher and fighter, whomever you encounter with your love and wisdom, he must flee or become like you! Baseness and weakness do not survive beside you.

How often were you near to me when you had long been far from me, and illuminated me with your light, warmed me so that my hardened heart moved again like the frozen wellspring when the ray of heaven touches it! I wished I could flee to the stars with my blissfulness so that it would not be degraded by what surrounds me.

I had grown up like a vine without a pole, and the wild tendrils spread aimlessly over the ground. You know how so much noble strength perishes among us because it is not used. I wandered about like a will-o’-the-wisp, assailed everything, was seized by everything, but only for a moment, and the inept powers drained themselves to no purpose. I felt that everywhere I was missing something and could not find my goal. Thus was I when he found me.

He had long expended enough patience and art on his material, the so-called cultivated world, but his material had been and had remained stone and wood, had perhaps of necessity outwardly assumed the noble human form, but my Adamas wanted nothing to do with this; he wanted men, and he had found his art too poor to create them. Once they had existed, those whom he sought, those whom his art was too poor to create – this he knew clearly. Where they had existed he also knew. He wanted to go there and seek their genius under the rubble, and thus to while away his lonely days. He came to Greece. Thus was he when I found him.

I still see him coming before me and regarding me with a smile; I still hear his greeting and his questions.

Like a plant, when its peace soothes the striving spirit, and simple contentedness returns to the soul – thus he stood before me.

And I, was I not the echo of his quiet enthusiasm? did not the melodies of his being repeat themselves in me? What I saw, I became, and what I saw was divine.

How powerless is the best-intentioned diligence of men against the omnipotence of undivided enthusiasm.

It does not linger on the surface, does not take hold of us here and there, needs no time and no medium; it does not need command and compulsion and persuasion; on all sides, at all depths and heights, it seizes us in an instant; and before we realize it is there, before we can ask what is befalling us, it transforms us through and though in its beauty and its bliss.

Joy to him whom a noble spirit has thus encountered in early youth!

O they are golden, unforgettable days, full of the joys of love and sweet activity!

Soon my Adamas initiated me into Plutarch’s world of heroes, then into the magical land of the Greek gods, then he brought order and calm to my youthful impulsiveness with number and measure, then he climbed mountains with me – by day for the flowers of the heath and forest and for the wild moss of the cliffs, by night so as to gaze at the holy stars above us and understand th

em in the manner of men.

There is a precious sense of well-being in us when our inner being thus draws strength from its material, distinguishes itself and attaches itself more faithfully, and our spirit gradually becomes capable of bearing arms.

But I felt him and myself three times over when, like shades from times past, in pride and joy, in rage and mourning, we climbed Athos and from there sailed across into the Hellespont, then down to the shores of Rhodes and the mountain gorges of Taenarum, through all the quiet islands; when longing drove us from the coasts into the gloomy heart of the ancient Peloponnese, to the lonely banks of the Eurotas, O! the dead valleys of Elis and Nemea and Olympia; when, leaning on a pillar of the temple of forgotten Jupiter, surrounded by oleander and periwinkle, we gazed into the wild riverbed, and the life of spring and the eternally youthful sun reminded us that man was once there and is now gone, that man’s glorious nature scarcely remains there, like the fragment of a temple or the image of someone dead in the memory – there I sat, playing sadly beside him, and plucked the moss from a demigod’s pedestal, dug a marble hero’s shoulder out of the rubble, and cut the thorn bush and the heather from the half-buried architraves, while my Adamas sketched the landscape that surrounded the ruin, so friendly and consoling: the hills of wheat, the olives and the goat herds hanging on the mountain cliffs, the elm forest that plunged from the summits to the valley; and the lizard played at our feet, and the flies buzzed around us in the quiet of midday – Dear Bellarmin! I would like to tell this to you as precisely as Nestor; I move through the past like a gleaner over the stubble field when the master of the land has harvested; he gathers up every straw. And when I stood beside him on the heights of Delos, what a day that was that dawned for me as I climbed the ancient marble steps with him up the granite wall of Cynthus. Here the sun-god once dwelled, amidst the heavenly festivals in which assembled Greece shone around him like a cluster of golden clouds. As Achilles threw himself into the Styx, the Greek youths flung themselves here into tides of joy and enthusiasm, and went forth invincible as the demigod. In the groves, in the temples, their souls awakened and resounded in one another, and each youth faithfully preserved that enchanting chord.

Hyperion

Hyperion